The Chinese Endgame in Ladakh

- sswatisingh1105

- Nov 21, 2020

- 8 min read

Recently, twenty Indian Army personnel, including the Commanding Officer of 16th Bihar Regiment, lost their lives at the hands of Chinese troops in the Galwan Valley of Ladakh. This was an unprovoked attack by the Chinese border troops on Indian soldiers, after confirming the implementation of the de-escalation plan by the Chinese in Galwan valley. The plan of de-escalation is based on a phased withdrawal of troops to their respective predetermined ground positions, were decided on June 6 during the corps commanders-level talks.

The incident represents a watershed in India’s relations with China and marks the end of a 45-year chapter which saw no armed confrontation involving loss of lives on the Line of Actual Control (LAC).

What is the issue?

1) The Indian and Chinese armies are engaged in the standoff in Pangong Tso, Galwan Valley, Demchok and Daulat Beg Oldie in eastern Ladakh. 1A) A sizable number of Chinese Army personnel even transgressed into the Indian side of the de-facto border in several areas including Pangong Tso.

1B) The actions on the northern bank of Pangong Tso are not just for territorial gains on land, but enhanced domination of the resource-rich lake.

2) The stand-off at Ladakh’s Galwan Valley has escalated in recent weeks due to the infrastructure projects that India has undertaken in the recent years. India is building a strategic road through the Galwan Valley - close to China - connecting the region to an airstrip.

2A) China is opposed to any Indian construction in the area. In 1962, a stand-off in the Galwan area was one of the biggest flashpoints of the 1962 war.

3) The border, or Line of Actual Control, is not demarcated, and China and India have differing ideas of where it should be located, leading to regular border “transgressions.” Often these don’t escalate tensions; a serious border standoff like the current one is less frequent, though this is the fourth since 2013. 3A)Both countries’ troops have patrolled this region for decades, as the contested 2,200-mile border is a long-standing subject of competing claims and tensions, including a brief war in 1962.

4) Reasons: The violent clash happened when the Chinese side departed from the consensus to respect the LAC and attempted to unilaterally change the status quo. 4A) It is part of China’s ‘nibble and negotiate policy’. Their aim is to ensure that India does not build infrastructure along the LAC. It is their way of attaining a political goal with military might, while gaining more territory in the process.

There is a dangerous parallel in history to the current India-China conflict in Ladakh. The violence in the Galwan river valley in June 2020, and the ongoing military confrontation in the Himalayas over the past six months, bears striking resemblance to a watershed moment in world history known as the Seven Years War. It is, therefore, important to examine the larger implications of this Sino-Indian rivalry on the polarity and distribution of power in the international system.

Experts have argued that China’s aggression in the Himalayas is an attempt to dissuade India from getting into an alliance with the United States. However, upon closer examination, the exact opposite is revealed. China’s attempt seems to be to drive New Delhi into Washington’s arms, use it as a precursor to consolidate a Sino-Russian alliance, and divide the world in two camps — a bipolar structure with the United States and China as the leaders competing for global hegemony.

China’s strategy to strike a fatal blow to a multipolar world, is straight out of the playbook of the Seven Years War, between Britain and France.

During the mid-18th century, the boundary between French and British colonial possessions in the present-day United States were not demarcated on a mutually agreed map, much like the Line of Actual Control (LAC) between China and India in the Himalayas. In 1753, Britain opposed infrastructure developments – a series of forts in the Ohio river valley — to check the assertive anti-status quo policy by the French.

Peaceful attempts by the British failed to restore status quo ante and led to a skirmish in which 10 French soldiers, including the commanding officer were killed. The French revenge on the British forces came shortly thereafter. Eventually, the first President of the United States, George Washington, who led the British army as a Lieutenant Colonel in that skirmish, surrendered to the French forces at the Ohio river valley. Diplomatic attempts to resolve the crisis could hardly reach a meaningful compromise, once blood had been shed.

The Ladakh conflict has followed a similar script so far. New Delhi’s peaceful efforts to halt Beijing from erecting structures on the disputed areas of the LAC were unsuccessful in the summer of 2020. Following this, India objected to the presence of Chinese structures on June 15, leading to a violent clash and the death of 20 Indian soldiers on the Galwan river valley, in addition to an unknown number of Chinese casualties. This was the first instance of blood being shed on the India-China border in over four decades. In retaliation, the use of special frontier force comprising Tibetan exiles by India, to capture strategic heights, along the LAC at Pangong Tso, is a leaf out of Britain’s strategy of working with local American Indians against aggressive French designs.

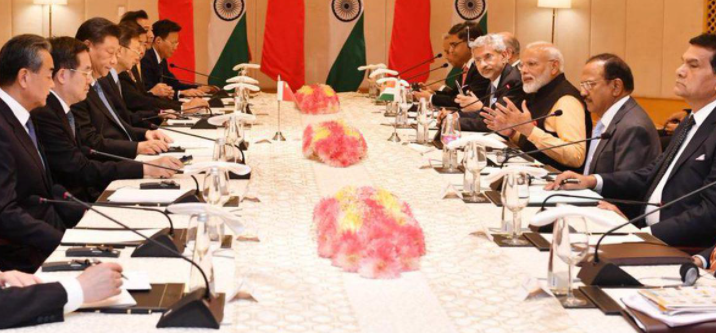

Two rounds of diplomacy at very high levels, between the defence and foreign ministers of India and China had limited success in reducing tensions, just as diplomatic efforts between Britain and France were not very successful. Although Beijing may have a stronger army than New Delhi, Indian Navy has operational advantages, and a history of being a maritime power, unlike the Chinese navy. These realities are reminiscent of the British-French military balance of power in the mid-18th century – while France had a superior army, British navy had access to key maritime chokepoints.

The Ohio river valley conflict eventually snowballed into the Seven Years War between Britain and France, leading to a rush for colonisation and global hegemony. The most significant development during this conflict was the British-Prussian alliance formation, followed by the Franco-Austrian alliance. Interestingly, this development came to be known as the “diplomatic revolution”, because it involved Britain and France, interchanging their erstwhile allies. It is along these lines, that if China’s aggression in the Himalayas provokes India to enter into an alliance with the United States, China can then use it an excuse for full-fledged military alliance with Russia, thereby splitting the Indo-Russian strategic partnership.

What lessons can India and China draw from the Anglo-French Seven Years War? Although Britain ended up being the victor, the Seven Years War took a huge toll on its economic and military resources. For France, the military campaigns only resulted in minor tactical victories. The jostling for power ended multipolarity and established a bipolar order of British-Prussian alliance against Franco-Austrian alliance. Therefore, pushing the current Ladakh crisis to its logical conclusion may end with an Indo-US military alliance followed by a Sino-Russian alliance.

Beijing is acutely aware that a war with China may well be the final nail in the coffin for India’s conception of strategic autonomy. Therefore, pushing India to the brink of war, is a well-thought-out strategy by China. Irrespective of the outcome, a war in itself may drive India towards a military alliance with the United States, allowing China to turn Russia against India, effectively breaking the Indo-Russian strategic partnership. Consequently, the Indo-US alliance and a Sino-Russian alliance, will end New Delhi’s vision of multipolarity and establish a transient bipolar world order. This is China’s endgame in the current Himalayan conflict with India.

JUST A GALWAN VALLEY CLASH OR A HIDDEN SIGNAL OF DANGER UNDER THE NAME OF BORDER CONFLICT?

Something bigger is afoot than just shifting the LAC a couple of km in Ladakh. The government must figure out what the Chinese game plan is and thwart the endgame before it is upon us.

Indian strategists must think several steps ahead of the Chinese if India is to defeat the challenge which is currently in the Ladakh region, but could spread elsewhere. After all, a large number of Chinese troops and armaments are massed in Tibet right along the Indo-China border. Even within Ladakh, the Chinese intruders have changed the goalposts a couple of times since the beginning of May, when they first turned up in huge numbers.

The pushing and shoving that marked their ingress in early May gave the impression that they were primarily targeting the north bank of the Pangong Tso lake.

The two countries' perceptions of the LAC along that bank have differed for years. So, that seemed like only a more belligerent repeat of past skirmishes.

But the Chinese were also pushing at the boundaries in the Hot Springs and the Galwan area at the same time and by mid-June, the Chinese had not only consolidated up to Finger 4 on Pangong Tso, the main action had shifted to the hitherto undisputed boundary in the Galwan Valley.

In the couple of days after the fight at Galwan on the night of June 15, the Chinese apparently consolidated fortifications right at the Line of Actual Control there.

In fact, according to most expert estimates, their new battlements at a major bend of the river are actually on the Indian side of the LAC.

The following week, it turned out that the Chinese had moved forward in the Depsang plain farther north and were approaching a bigger strategic prize -- the highest airfield at Daulat Beg Oldi. That airfield is very close to the Karakoram Pass on the India-China border -- the established border, not the Line of Actual Control skirting Aksai Chin.

Lieutenant General Rakesh Sharma (retd), a former commander of the Leh-based XIV Corps and currently a Distinguished Fellow at the army's think-tank, holds that the Chinese perhaps want to wrest that corner of Ladakh around DBO from India. The way General Sharma sees it, having a road through DBO would substantially reduce the distance the Chinese have to travel to connect the main CPEC route, which runs through the Khunjerab Pass.

That may not turn out to be the Chinese intention, unless they want to reorient the road directly east or southeast (via Tibet) to reach the heart of China. Crossing from Aksai Chin to the Xinjiang province would be a long loop. Plus, "they already have a fabulous highway over the Kunjerab" Pass, as Major General Somnath Jha (retd), a former commander of the brigade that holds Eastern Ladakh, points out.

The differing viewpoints of the two retired generals, both very intelligent men, illustrate the extent to which the country's strategic community is guessing in the dark about what the Chinese actually want. For the moment, India's strategists seem to be at sea, perhaps more so within government than among retired officers. The established narrative so far is that the Chinese are engaged in what General Bipin Rawat, the chief of defence staff, called 'salami slicing' when he headed the army. That view may be missing the wood for the trees. For, there are tell-tale signs that something bigger is afoot than just shifting the LAC a couple of kilometres in Ladakh.

Sadly, the array of Indian intelligence agencies seem to have been caught napping. As General Sharma points out with a tone of disbelief, two divisions of the People's Liberation Army just turned up in Aksai Chin in May.

"We used to say it will take them two months to cross to it," General Sharma observes, "But two whole divisions just appeared there."

It seems that the range of intelligence paraphernalia and agencies did not have advance warning nor even spotted them when they were physically moving in.

As it happened, even the normal springtime deployment of the Indian Army was not in place at the edges of Aksai Chin when that happened. Apparently, those who are paid to apply their minds to tactical possibilities prioritized covid-related restrictions.

They evidently did not think the strident Chinese opposition, at the United Nations Security Council and elsewhere, following the Constitutional changes with regard to the erstwhile state of Jammu and Kashmir last August, might possibly lead to coercive action on the ground. It is futile to cry over split milk, but the government needs to ensure that the intelligence apparatus pulls its act together at least now.

A top priority should be to figure out what the Chinese game plan is and to get ready to thwart the endgame before it is upon us, possibly in early winter. This requires insightful analysis as well as the various kinds of information gathering resources at the government's disposal. For, given the shifting Chinese goalposts, Indian strategists need to think several steps ahead of what is obvious on the ground.

Heavy deployment ought already to have been organised in the Depsang area while the Galwan operation was being planned. It is possible that Demchok further south and other sectors of the long boundary between the two countries could be the next targets. India should keep in mind the lessons of the 1965 War, when Pakistan intruded in Kutch to draw Indian forces to the other end of the India-Pakistan border before they went for their real objective - Jammu and Kashmir.

<a href="https://www.sharmaacademy.com/">Sharma Academy</a> <a href="https://www.sharmaacademy.com/upsc-coaching-in-indore.php">UPSC IAS</a> <a href="https://www.sharmaacademy.com/mppsc-coaching-in-indore.php">MPPSC</a> <a href="https://www.sharmaacademy.com/best-mppsc-online-coaching-classes-in-indore.php">mppsc online coaching classes</a> <a href="https://www.sharmaacademy.com/mppsc-tablet-pendrive-sdcard-course-online-prepration-notes-study-material.php">online mppsc coaching classes</a>

good